Crossing the ocean of my ignorance |

|

...postpone reading Nietzsche for the time being; first study Aristotle for ten to fifteen years.– Martin Heidegger 1

As a researcher, either you won’t understand something and you will feel stupid and like a worm, or you will understand something and think it’s too trivial and hence still feel like a worm.– Simon Peyton Jones

I was much further out than you thought– Stevie Smith

And not waving but drowning.

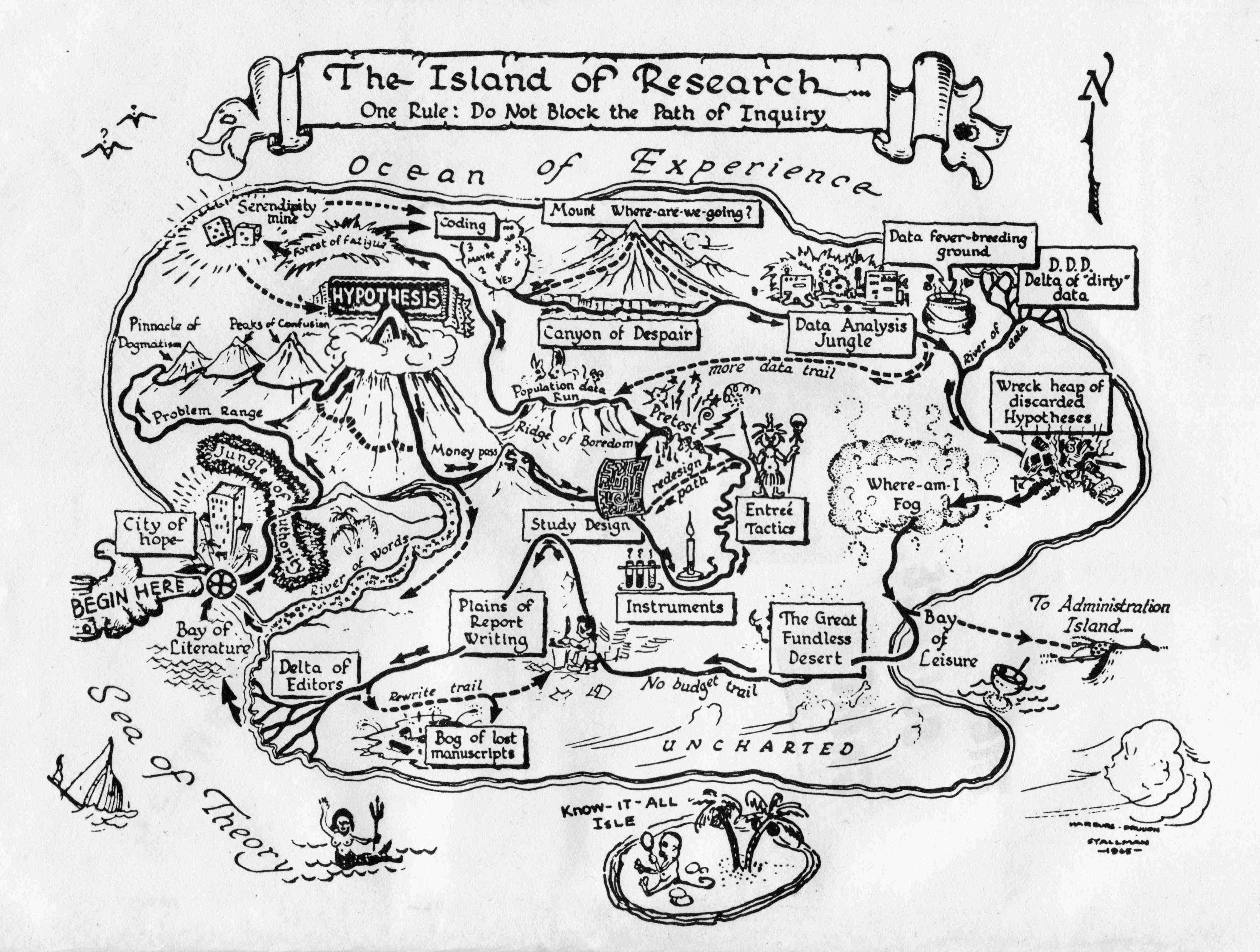

What do you need, to do new things? Imagine you’re a junior researcher; a scientist; a dry-lab scientist; a Machine Learning person. For good and bad reasons you want to publish in Deep Learning, a decade-old bandwagon which continues to steamroll your field. You’re rolling in the deep. How do you get to work?

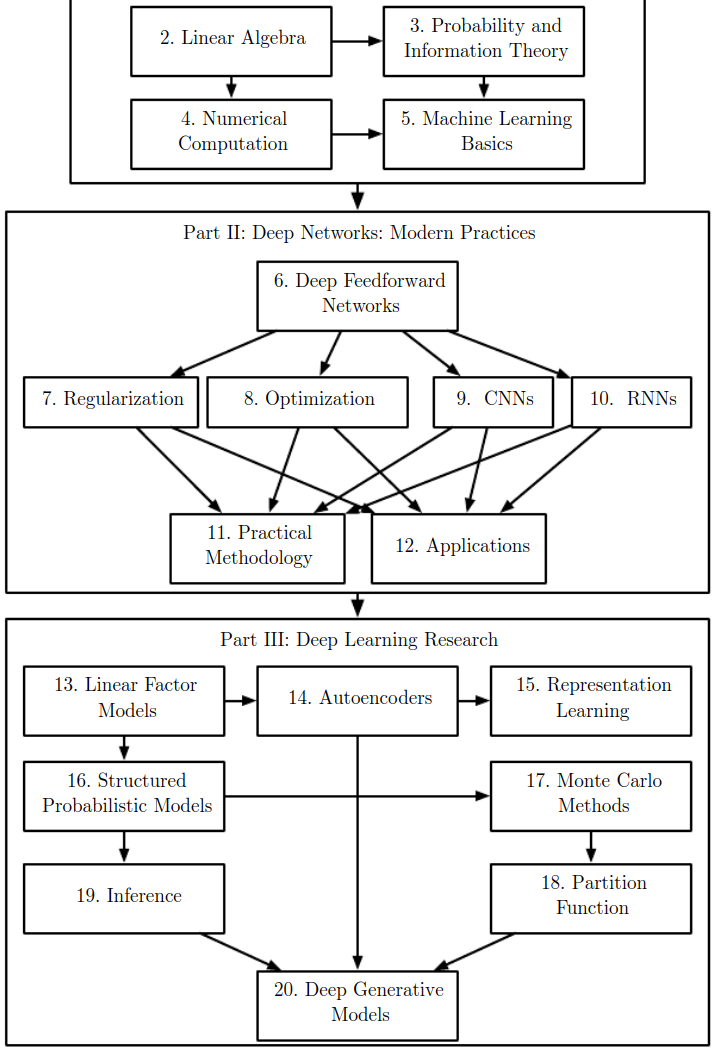

A natural answer is to start at the beginning: go read the underlying mathematics.

OK, say you go off and do that. You’re not happy with your understanding: you can feel the aching gap in your knowledge of say linear algebra - that your looking at all those matrices actively concealed something important - but you figure it’s enough for now.

It takes a month or six. Can you do new things now? No: you have to learn how to actually implement things. Brilliant people have built easy tools for you, so you learn one of those and reimplement some big papers. This is harder than it sounds, and you actually don’t manage to reproduce half of the results. You add 3d6 unease and self-doubt.

That takes a month or two. Can you do new things now? No: you need a good idea. Where do you get those? ‘Related Work’, I guess. You go read. Later, your mouldering bones are discovered at your desk, with 200 tabs open and the Colab Disconnected modal still burning on your screen.

So much of the foundations I do not understand, and it would take a lifetime to fully understand them (and by then I’d have forgotten the first bits). With such a burden, how does anyone do new work? Well, by not doing any such thing.

- you have to just start

- you’ll learn it when you need it

- most research is not done alone

- most researchers don’t remember the low-level stuff, and don’t have to

- you don’t have to focus on one thing

- forcing yourself to work on something has large costs

Even after we reject foundationalism, the practical problem remains: what to learn, and how? I’ve been trying to think new things for about 6 years, but only recently got any good at it. Here are some things that may have helped:

Requisite attitudes

The Neurathian bootstrap

We are like sailors who on the open sea must reconstruct their ship but are never able to start afresh from the bottom. Where a beam is taken away a new one must at once be put there, and for this the rest of the ship is used as support. In this way, by using the old beams and driftwood the ship can be shaped entirely anew, but only by gradual reconstruction.

Beginning at the beginning, craving absolute foundations, mostly leads to paralysis. Sometimes this is because it takes too long to reach the frontier from the foundation; sometimes it’s because the foundation is missing or impossible.

To live, you have to ignore things. So bite off a chunk of reality and ignore the rest. Manuel Blum:

When working on a PhD, you must focus on a topic so narrow that you can understand it completely. It will seem at first that you’re working on the proverbial needle, a tiny fragment of the world, a minute crystal, beautiful but in the scheme of things, microscopic. Work with it. And the more you work with it, the more you penetrate it, the more you will come to see that your work, your subject, encompasses the world. In time, you will come to see the world in your grain of sand.

People don’t talk enough about what they ignore. One exception: Andrew Gelman, one of the most influential statisticians alive, never bothered with measure theory, the deep generalisation / justification of probability theory.

The raft is our lack of fear at the lack of raft.

Comparing down

The above isn’t about impostor syndrome, except insofar as I delude myself that others are not ignorant. I take impostor syndrome to be the subjective feeling of being inadequate relative to those around you. I’m talking about the objective sense in which no one has anything more than a piece of the puzzle; and yet some of them still manage to do new things. (To get a sense of how rough the subjective and objective problem is, note that PhD study breaks a quarter or a half of the smart people who try.)

Anyway: I had a very distorted view of how much an average PhD actually knows. Just as an undergraduate degree only shows you once had a small degree of knowledge on one or two topics, so too getting postgraduate funding only means that you’re not totally dense and callow. This is good news! Not-totally dense and callow people manage to do many of the coolest things.

Unlearning education

Books should follow science; science should not follow books.– Francis Bacon

I was lucky; by being born in the right time and right place, I got huge amounts of free education.

I was unlucky; an education was not what I actually needed; education trains you for the wrong task, in the wrong way. The ability to do research correlates with doing well on tests. But it is probably not well served by the current degree of optimising for tests, reading, and mere recall.

There are multiple mismatches: it focusses your attention on solved or toy things; it emphasises understanding old things rather than creating new things; it expects you to do your best, not to solve things; it mostly doesn’t let you follow your curiosity; it mostly doesn’t train you to handle the gross uncertainty of research. (Outside of mathematics, there is no marking scheme - not even peer review, not even awards at conferences. Maybe 10 years later you’ll get some sense of whether you actually succeeded.)

Question first, not books first. Learning is best and most lasting when in the service of a goal you actually care about: not “better grades”, not “impress distant superior”, but “I want to build x”. When it is part of you.

PhDs are still pretty artificial (they make you work ~alone, on one pre-specified topic which has to look sensible and follow an existing programme, with deadlines, and you’re fed ideas), but at least their goal is not a total dead-end.

It’s not easy to unlearn tutelage, but at some point in your first few actual projects you might manage it.

Ideas are cheap

One useful piece of startup culture: “you have to ship”. It is not that your perfect idea is ruined by imperfect implementation: your idea is nothing until it exists; all implementations are an improvement over an idea. 2

Mechanisms

The above is about fixing your head. This bit is about how the vastness of the ocean actually ends up not mattering:

Abstraction as testimony

Some abstractions actually allow you to ignore what’s underneath; some boats don’t sink that quick. I’ve been playing with the internals of Pytorch recently. How many people understand the Tensor class? A couple hundred probably, for say 100,000 users of it, and who knows? a billion downstream users. In fact, most good software is about shielding you from details: even the statement a = 1 is pretty computationally complicated. The world couldn’t work without the glory of testimony like this.

Collaboration

Even once you’ve selected a level of abstraction, trusted the bulkheads to hold, you can still split the work further: laterally across co-authors who are good at different parts. This is division of labour again, one of the most powerful social forces.

The average paper now has about 5 authors. Some of this is down to a deflation of what it takes to count as an author, but the rest is good stuff. One (conceptually) simple solution to the replication crisis in social science would be to require a statistician to be on every project, at least in the experiment design.

Momentum

Ideas generate ideas, success generates success.

In Spring, I worked on a coronavirus modelling project. In writing it I collected 15 major ideas that we didn’t have time for, didn’t have data for, which didn’t fit into the scope of that paper. One week after submitting it, a subset of that team wrote another paper on the methods used, including 3 or 4 completely novel ideas and tests and proofs. We could do this 3 or 4 more times without a hint of ‘salami slicing’, bad behaviour. If we could only sustain the energy.

Slack

You waste years not being able to waste hours– Amos Tversky

One of the perversities of academic life is the absence of slack: spare time for just playing around. I won’t go into this here (see here instead), but here’s a nice story. A young mathematician recently cracked a notorious problem as a side-project, no deadline, no particular expectation of success, almost an etude.

you have to have a question

https://acesounderglass.com/2020/06/09/where-to-start-research/

Teaching as learning

You think you know when you can learn, are more sure when you can write, even more when you can teach, but certain when you can program

Consider the grad student in teaching mode… When the professor asks them questions, they’re Expected To Do Their Best; when the undergrad asks them questions, they’re just expected to answer. In the first case, they’re expected to try; in the second case, they’re assumed capable, an assumption that fades into the background.

The bureaucracies act as if you can only teach once you are a master. But I often feel that I don’t understand anything until I try to explain it to someone else - hence this blog. Yet another unforced error of ordinary education: you’re not allowed to learn through teaching until it’s over.

“You learn the prerequisite in the next course.” And I learn the prerequisite when I am allowed to teach the prerequisite.

See also

- Laura Deming’s rage.

- Matt Might’s ways to fail

- I think this post obsoletes some of the above.

- Karnofsky

- Schwartz

- Peyton Jones, ‘How to Write’

- Steinhardt, ‘Research as a Stochastic Decision Process’

- Abram Demski in the Field,

- Nerst, Decoupling

- Alexander, ‘Ars longa, vita brevis’

- Holden, ‘Why Can’t I Reproduce Their Results?’

- Soares, ‘Stop trying to try and try’

-

...in order to understand the Epic of Gilgamesh, you'll have to first comprehend the cave paintings and sculpture produced during the Upper Paleolithic. Without a full grasp of the cave paintings at Lascaux, you'll never be able to contextualize the oral tradition that produced Gilgamesh, leaving you without a full knowledge of the Septuagint, making your reading of Kierkegaard incomplete, making your reading of Heidegger & Derrida faulty.

Of course, you'll need to learn Proto-Indo-European.</a> - There are subtleties here, about data fumes, info hazards, idea inoculation, and poisoning the well. But unless you're working on very strange things these are unlikely to apply.

Comments

Max commented on 03 July 2020 :

Later, your mouldering bones are discovered at your desk, with 200 tabs open and the Colab Disconnected modal still burning on your screen.

Hahaha. Thanks for this, I could relate to this strongly and feel like it helped me articulate some of my struggles with my PhD. There exists so much work already, everything is somewhat relevant to my thesis and it seems so impossible to contribute to anything.

Tags: research, writing, self-help, phd